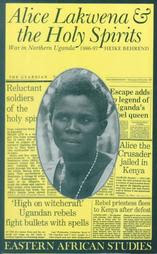

Heike Behrend, Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirits: War in Northern Uganda, 1986-1997 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1999), 210 pp.

Heike Behrend, Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirits: War in Northern Uganda, 1986-1997 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1999), 210 pp.When most people think of cults in Uganda, three groups come to mind: Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army, Joseph Kibweteere and Credonia Mwerinde's Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God, and Alice Lakwena's Holy Spirit Movement. This book seeks to chronicle the formation, growing success, and ultimate failure of Lakwena's movement. As an anthropologist, Heike Behrend seeks not only to describe this cult, but also to set it in its historical and social context.

The author begins by struggling through the issues of writing an anthropological study on Alice Lakwena and the Holy Spirit Movement. Then she recounts the history and development of the ethnic identity of the Acholi people from Northern Uganda. Next, she writes about Alice Auma as she becomes the medium for the (male) spirit Lakwena and begins to form a military mobile force to purify the land from evil in the midst of political and military turmoil. This history continues to unfold from the humble beginnings in Paraa and Opit to the several thousand member army marching toward Uganda's capital. Finally, the downfall and final defeat of the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces is summarized. The remainder of the book is given over to further analysis of what happened, as well as briefly looking at developments since the fall of the Holy Spirit Movement.

As one who is in the process of becoming a missionary in Uganda, I found this book to be exceptionally informative. I've learned a lot about the history of Northern Uganda generally and of the notorious Lakwena's Holy Spirit Movement specifically. And by reading about the context in which these events took place, I was able to better understand the traditional beliefs and practices of East Africans as well as the syncretism that forms from combining these traditions with elements of Christianity.

At the same time, this work is an academic tome and can be hard to read. The author assumes a certain amount of previous knowledge of anthropological and sociological concepts and issues. She also regularly points to and interacts with various scholarly theories. Thus, this book is not an accessible treatment of the history of Lakwena and the Holy Spirit Movement.

As a result, one may or may not find reading this book to be beneficial. Anthropologists, missionaries, and others looking to learn more about this important sect in Ugandan history will surely want to read Behrend's study. But more casual readers will likely find themselves lost in the scholarly discussions and analysis. For those willing to dive in and develop their understanding of these key events, I recommend consulting this work.